Wim’s Movie (Wim Wenders and Nicholas Ray)

1. There are two unforgettable lines in the films of Raymond Nicholas Kienzle, aka Nicholas Ray, aka Nick. In 1957, in the Libyan desert of Bitter Victory, Richard Burton observed bitterly: “I kill the living and save the dead”. The year before, James Mason wanted to kill his son screaming “God was wrong!” (wrong to stop Abraham’s hand). The film was Bigger Than Life. These two lines are a program unto themselves. Mason’s line, in Ray’s cinema, is the version of the father, a father who has become insane, threatening, unfit: a deviant. Burton’s line is a son’s impasse, the double bind that he cannot escape, at least not unscathed: kill the living father or save him dead. The subject of Ray’s films is less revolt than the impossibility of revolt, the endless dispute between two men, a young one and an old one, the adopted and the adoptive. The old one “plays” the father, takes the blows, fakes his death, deprives the “son” of his revolt. The hystericised son must sustain the father’s desire, and therefore attribute a desire to the father. In this respect, Wind Across the Everglades is a wonderful film. Nearly all of Ray’s films tell this story, all end badly, or rather they do not end, or on a fake and hurried happy ending. This, the forced alliance toward filiation, or filiation experienced as an alliance, was the cinema of Nicholas Ray. But at the dawn of the 1980s, it is also a way to narrate the “history of cinema”.

2. In Wenders’ film – this Nick’s Movie that became Lightning Over Water before becoming Nick’s Movie again at the very last moment – Ray has, for Wenders, become a Ray character. This film marks the culmination of the renowned politique des auteurs, a politique invented (here, in France) to defend films like Ray’s and which was itself formulated in a strange, oedipal way: a failed film by an auteur was always more interesting than a successful film by a non-auteur. In other words, the auteur is always right since we are talking about the father figure here. Today, we know what this politique des auteurs has become: on the commercial side, it’s the forced marketing of signature effects, and on the filmmaker side, it’s the often hypocritical cult of the dead. Nick’s Movie is all this but also more than this: less a film about filiation than filiation made film. Wenders believes himself incapable of separating the two films: the one desired by Ray and the one commissioned by Coppola. On the one hand, an auteur’s film, a work that is European, open, even gaping, poor, experimental: a documentary on New York’s loft apartments. On the other, a craftsman’s film, professional, meticulous, expensive, a revival of the California found in film noirs and Dashiell Hammett’s novels. Wenders has “managed” to locate himself simultaneously in two extreme situations for a contemporary filmmaker: not to have chosen your subject and to have been chosen by your subject. But the two experiences communicate with one another: the young German filmmaker learns in the end from the subject Ray the skills that he needs to confront the Coppola machine. He turns a part of America – a wounded, dying part – against America itself. He is not the first one to do this: there is already a long history. In Contempt, Godard played Lang’s assistant on the set of The Odyssey for a paranoid producer called Prokosch. Lang was a fallen old master, a monument of cinema but also someone who had suffered a lot in Hollywood. Then we saw Welles in Chabrol’s film, Fuller in Godard’s (and Wenders’), Fassbinder playing in Sirk’s university films etc.

3. I am not talking about the influence of the older filmmakers on the new ones, or of cinephile generosity (although we have seen Scorsese supporting Minnelli and others trying to help Tourneur produce a new film). I am talking of the presence – the physical presence – of certain filmmakers in films of the new wave (the French New Wave firstly, and then the Italian and the German ones). And not just any filmmakers, but those, born in America around 1910, who had their careers cut short, stymied or simply destroyed. Between 1960 and 1965, filmmakers as important as Welles, Mankiewicz, Kazan, Sirk, Ray and Fuller fell silent or lost the favours of audiences, and therefore of the studios. They had often become too singular or too modern for Hollywood. At the time, we saw it as the consequence of the crisis in American cinema or the malice of the Majors. But this phenomenon was also symbolic. For the first time in the history of cinema, a generation born in cinema (unlike the previous generation, that of the pioneers) no longer works and has lost the right to say “filmmaking, our profession”. Faced with the exceptional longevity of their elders (Dwan, De Mille, Walsh, Ford, Hawks, Hitchcock), their horizons have shrunk, their time has gone fast, and even though they still have a lot to say and to film, they have been reduced to silence.

|

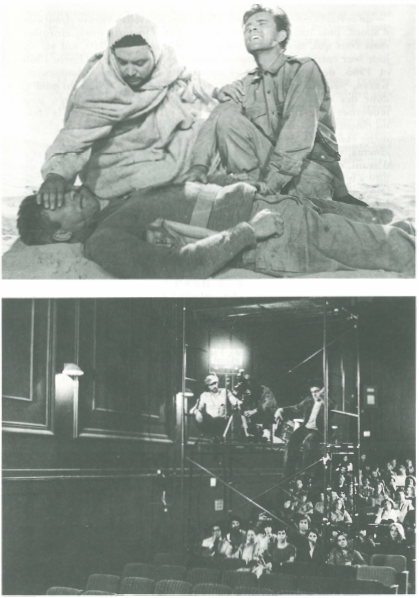

| Illustrations from La Rampe. Bitter Victory (top) and the set of Nick's movie (bottom). |

4. This had never been the case, at least not in America. And it happened at the time of the emergence of European “new waves”, of the first cinephile filmmakers. We hadn’t really noticed at the time that these young auteurs, who had invented the said politique only to be its beneficiaries, weren’t sure at all that filmmaking would be, for them, a profession. It is not impossible that, faced with the demands of modern cinema (which focuses on experience rather than know-how), the very idea of a profession came across as regressive, outdated. Yet, twenty years later, despite the cold war that they are engaged in, Godard and Truffaut have this in common: they have never stopped filming, with or without an audience, for the audience or against it. Filmmaking is their profession. As Truffaut says: “what makes me happy about making films is that it offers me the best possible use of my time”. But Truffaut made sure this was true, true for him. It likely will be the same for Wenders or Bertolucci, Fassbinder or the Straubs. In Europe, what is decisive is not box-office success but the capacity of filmmakers to build the machine which, despite occasional failures, can continue to reproduce itself. This is how an aesthetic can take shape. But there is no such thing in the USA (except perhaps for Cassavetes): the broken generation of the 1960s didn’t know how to operate in any other way – it was Hollywood or bust. If not for his lifetime contract with MGM, Minnelli is prematurely finished, Kazan and Fuller have taken to writing, Sirk has comeback to Europe, Tourneur just died in France, Ray has sought exile, Welles has been showboating, and even Wilder, Preminger and Mankiewicz are facing difficulties. I believe that the young European filmmakers have then exorcised their fear of not being able to make films forever by granting their American elders a sort of filmic survival. So as to truly be their heirs. A paradox: The American Friend is always the case of an American father who has run into trouble.

5. I find the word “cinephilia” too limiting to explain this phenomenon. Nor is it a case of an abstract history of forms or a list of influences (because genuine influences are always oblique). It’s about the status of these filmmakers, their history, where they come from and the mythical history they have fabricated for themselves. It’s also about something that cinema, and only cinema, can do – better than painting – because it is a figurative art, meaning that it can make figures come back, come back from a past where they have represented something unique for someone else. Actors are those privileged figures: they are essential to the dialogue between filmmakers. Because of them, cinema cannot be the mere succession of styles or schools, and the phenomena of filiation take shape through nostalgic, ageing images of the same bodies. The body of the actor spans all cinema, it is its true history. This history is never told because it is always intimate, erotic, made of devotion and rivalry, of vampirism and respect. But as cinema gets older, it is this history that films bear testimony to. The encounter between Ray and Wenders and the film born of this encounter are a chapter in this history. Comolli had clearly seen – in a text in Cahiers that was mistaken for a joke – that, in 55 Days at Peking, Ray played the role of a paralysed American ambassador, as a metaphor for his situation as the auteur of a film that was getting out of his hand. End of his official career as a filmmaker and beginning of his career as an “actor”. An exhibitionist actor who was aware of it and who watched himself age in the films of others, and sometimes in his own films (see the perfectly named We Can’t Go Home Again). What was modern was the survival of a filmmaker as an unemployed body, a crazed guest star, a ghost. And the most modern, in this sense, was Welles. Conversely, what was classic was the elision of the body of the filmmaker (or its ironic presence: Hitchcock): what is more unthinkable than the appearance of Mizoguchi, Ford or Hawks in their own films? Nothing. Toubiana was right to say (in an article for Libération) that Ray has bequeathed his body to Cinema like others bequeath theirs to Science. Except that Cinema doesn’t exist, it’s always a filmmaker – and in this case, it was Wim Wenders.

6. This is why the attitude that consists of criticising Nick’s Movie for moral reasons seems to me short-sighted if not unjustified. What is abject in cinema is the figurative surplus value, the “supplementary image” that a protected auteur extracts from the spectacle of an exposed actor (exposed to ridicule, indecency or death). It consists of ignoring the non-reciprocity of the filmic contract. But what happens if the exposed actor, having also been an auteur and understanding both sides, has generated this spectacle, if he has desired it? And if he has bequeathed this spectacle as well? Opposite Ray, there is another introverted, rather ill-at-ease actor: Wenders. The game is equal between them because they have something in common: they are both posers. Since the very beginning, Wenders has been a filmmaker of seduction, not exhibition but a discreet, imperceptible posture where the most neutral of images confer to those within the image and to the one who has put them there the secret pleasure of knowing that they are being seen or caught “not posing”. A “double posturing” that irritated me in Wenders’ first films and in The American Friend but I like the fact that, instead of cultivating it further, Wenders has made it the very subject matter of Nick’s Movie. For one gets the feeling that the encounter between Ray and Wenders is turning out to be a genuine encounter. Between father and son probably, between peers for sure. Ray knows the stakes of this game of hot cockles between the one who poses and the one who is made to pose, between the one who kills and the one who dies (in Bitter Victory, also featuring in The American Friend: it’s the one dealing the fatal blow who screams, and who screams in place of the other). Just watch the end of the film and the exhaustion on Ray’s face. There is nothing left to say, he says “Cut!” Wenders (off-camera) says, “Don’t cut!” Ray: “Don’t cut.” It’s a game where no one wins but which saves the film from pure and simple necro-cinephilia. There is such an awareness of the camera among everyone involved that it is as if its presence became the only driving force of the film, pushing the viewer to the periphery, depriving him of his “slice of death.”

7. We believe too easily in the power of the camera to cut through poses, to strip away masks. We are too quick to cry rape. But a camera merely captures masks and reflexes, hidden behind or beyond the “role”. “Live broadcast” is merely the name given to a technique for recording images and sounds. There is no live per se. “Live,” we witness the making of a subtle body, formed of material clues resulting from the idea that the body exposed to the camera has of itself. A subtle body, the vague hope of a mask, a turmoil, a mutation, a hieroglyph: nothing simple. This is more than actorly know-how (if it were the case, then everyone would be an actor) because this subtle body, this protecting body, this extra layer of skin, is the same as the other, barring a hymen (but the hymen is solid). That is why I think Wenders was right to edit Nick’s Movie again. The version shown in Cannes was a long, uneasy and rather chaotic film that could be defended only if we thought that it was the reality of the shooting that was being captured. A shooting that no one had wanted, an orphan film that no one wants to take responsibility for. In a scene that has disappeared in the final cut, the editor could be seen trying to put the film in order. I had the impression that the film was neither Ray’s (who died before the end of the shoot) nor Wenders’ (who, in another scene that has disappeared, is criticised by the team for abandoning the film and setting off to California to attend to his other film, Hammett), but that of the editor, Peter Przygodda, and that the film bore witness to his difficulties and sufferings. Przygodda emphasised Ray’s moribund figure, the stalling of an uncertain shoot, the misery of the team gripped by helplessness and a desire to do well. It is clear that Wenders has betrayed something in editing the film again: Przygodda’s film, the raw documentary. One could find it regrettable, of course. But it’s certain that, in doing so, Wenders has found the real subject of his film, neither Ray’s death, nor the film in a film, but the truth of his relationship to Nicholas Ray. Recall the magnificent scene from Kings of the Road where Zischler, having returned to see his father and unable to talk to him, designs the front page of a newspaper (he is a printer) while the father sleeps. Writing triumphs where speech fails. “While father is sleeping.” While Nick Ray is dying: benefitting from an intermittence. In the final version of Nick’s Movie, such is the presence of Nick Ray: intermittent, mysterious. Sometimes it even seems that he has been long dead. And I love this scene (which could be deemed too explicit but it’s precisely what I like with Wenders: the ponderousness of explanations) where Wenders dreams that he is in Ray’s sickbed himself and that Ray is watching over him: a zombie-like Ray, attentive, slightly comical, like a ghost out of Kurosawa.

8. Wenders has said that he wanted Nick’s Movie to eventually be a fiction film. This is why he has undone his friend’s (Przygodda) edit. It’s not just a difference in style or a commercial concern, it’s a question of content. There may only be two great subjects in cinema: filiation and alliance. Ray and Wenders have the commonality of trying to mix, conflate and swap the two. I said at the beginning: filiations experienced as alliances or forced alliances toward filiation. Is Wenders Ray’s friend or his heir? His decision to renounce documentary devotion for fiction shows that he has opted for filiation, a filiation that he has the heart to accept. That is how I interpret the return of Wenders’ style in the final cut, including his quirks and facile choices (especially the musical bridges). As if he told himself, at one point, I am going to make this film such that the Officiel des spectacles* can summarise it as: “An elderly man and a younger one, linked by a strange friendship, attempt to make a film together, but the former dies prematurely…”. The film had to become anonymous again. The dead body had to be nondescript, embalmed. The only way to respond to Ray’s perverse injunction (something like: I demand that you betray me) is to be a good son, a good cine-son.

* Well-known weekly printed magazine listing all the cultural events in Paris with short summaries (translator’s note).

First published in Cahiers du cinéma in April 1980. Reprinted in La Rampe, Gallimard editions, 1983. Translation by Laurent Kretzschmar and Srikanth Srinivasan.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments are moderated to filter spam.