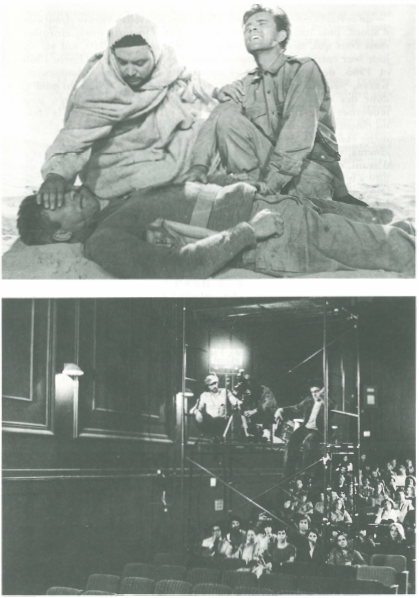

Audience at zero

If his films were loved by a section of French film critics in the 1950s, if Fuller was endorsed by the Cahiers as a modern filmmaker, it is because he was, more than any other American (except Welles), obsessed with the contemporary. Even when he was narrating past events, he always knew how to create this impression of “for the first time”, of the cinema at its beginnings. As if, before him, no one had ever filmed, nor seen any films. On the one hand, Fuller was interested in the secrets and paradoxes of History (his heroes are always impostors: a fake baron, a fake gangster, a fake Sioux, a fake madman). On the other, his stories always had a founding dimension. His first film, I Shot Jessie James, stages a man destined to act out again, for the theatre, events that he had been the hero of. Also, at the end of Run of the Arrow, this statement to the audience: “the end of this story can only be written by you.” Fuller, both a war reporter and obsessed educator, starts with this idea that the audience knows nothing, or almost nothing. Telling in a few words who the Baron of Arizona, Sergeant O’Meara, the Werwolf, or Hitler is, Fuller never builds on the supposed existing knowledge of the audience. He considers the audience to be, like him, self-taught and in a hurry. So much so that educated and self-righteous audiences, offended to be deemed more ignorant than they are, have always hated Fuller’s films, finding them basic or simplistic, and covered them with insults. What is disturbing with Fuller (or, for others, what is stunning and convincing) are less his ideological convictions (clearly, Fuller is not left-wing, loves his country and hates communists) than this concoction between news and fiction. News: everything that has a name (Fuller is obsessed with proper nouns); fiction: everything that is wearing a mask (nothing excites him more than double-dealings).

This concoction is not an ellipsis, that elegant way of gaining time. It is something else. Again, in Run of the Arrow, how to quickly show that the Civil War just ended? One could show the front page of a newspaper, or a distressed extra announcing the news, but Fuller is not interested in this type of speed. What interests him is to film Lee’s surrender, played by an extra, walking quickly, without grandiloquence, toward another extra. The historical event in itself, but as an insert.

This is the modernity of Fuller: the vertigo of the contemporary and the temporary lack of perspective on things. In a small, tiny-budget but admirable and prophetic film (Verboten!) he joins the Rossellini of Germany, Year Zero, and we still think of Rossellini when seeing The Big Red One. The soldiers and the audience discover at the same time the war, and much more than the war: the landscapes and the populations that serve as background to the war. We think of Godard too, except that Godard’s passion for denotation (calling a cat a cat) always threatens to prevail over the desire for storytelling. It is the exact opposite with Fuller: storytelling will prevail over everything else, will distort and divert everything. J.-L.G. narrates very little; S.F. narrates too much. One slows down, the other forges ahead. But the result is the same: they both become marginal, dangerous, and unsavoury filmmakers.

Impossible not to tell a story

So there was an “auteur” Fuller, an independent that the Hollywood machine ended up rejecting, a “European” Fuller if you will. And there was also an “American” Fuller, super-American even, less because of his political ideas than for his ability to heat up to the point of incandescence a fundamental aspect of American cinema: the impossibility not to transform everything into a story. Into a founding story moreover, a founding of the American identity. Fuller is devoted to fiction like others are devoted to drugs: beyond any taboo, any decency. He is “hooked” on fiction.

This fury was freely unleashed in the B movies of the 1950s. Paradoxically and against all expectations, it is this fury which prevented Fuller, who was ahead of everyone else, from reaping the benefits of the fires he had contributed so vigorously to starting. He lacked the taste for comfort, the art of arranging a “good place” for his audience in order to unify it against something (that’s what Penn, Peckinpah, or Pollack will know how to do); he wasn’t ideological enough. It is a paradox because ideology (ready-made speeches, idiotic propaganda, doublespeak and clichés) is his very topic, his preferred subject. This is another common point with Godard: he is both interested and horrified by political-speak. His films are pyrotechnical machines that stem from the tongue and set fire to speeches.

A necessarily ambiguous fire. During the Second World War, the journalist Fuller and the educator Fuller become one: he writes novels that soldiers read at the front, he must speak with the words of the tribe. War for him is perhaps just the extreme experience of the richness of sensations and the insufficiency of language. And to feel “in the present” one must speak with the words of everybody, the words of the GIs, the words of the media, while at the same time experiencing in a barbaric and refined way the inadequacy of these words with what is really happening. To question these words or to put them in quotation marks may raise the level of debate and intelligence, but it is a loss to the vertigo of feeling in the present, meaning to live. Fuller’s films start from what seems stable, fixed, erect and in costume, so a typical American worldview (a spontaneously racist worldview), and destroy along their way any sense of belonging or identity. More through an excess of fiction than out of critical distance. I don’t believe that the great Americans (Griffith or Welles) proceeded in any other way: never by putting quotation marks on the words of the tribe but rather through malfunction, excess or waste.

As for Fuller, he will go to the end of the idea of catharsis which is the necessary consequence of this fury of storytelling. Catharsis allows one to live with what shouldn’t be (seen) repeated. It has nothing to do with the “work of mourning”, this suspicion that between fiction and document, dream and proof, one must invent new distances and new rituals. Modern cinema, which was built from the work of mourning (Syberberg, Godard), has been European. But not American cinema which is always forging ahead toward catharsis (The Deer Hunter). In-between the two, Fuller is the only one who dared, twenty years before Holocaust, to bring together in the same film (Verboten!) these two types of images: stock-shots from the Nuremberg trials and images from his own B movie.

The danse macabre as film form

The Big Red One is therefore, in its current form, a traditional war film, superbly filmed, precise and dry: a film “like they don’t make anymore”. But what we can guess about the original project leads us to imagine a wider, disproportionate film: the crossing of the entire Second World War, seen through the successive missions of a regiment, of a squad of four men plus one, “the Sergeant”, played by Lee Marvin, devoid of any expression. These four indestructible characters cross countries they don’t know (Algeria, Sicily, France, Belgium, Czechoslovakia, and finally Germany), meet other soldiers, friends or foes, collaborators or resistance fighters, and in the end, it still comes down to them to free, open and discover the death camps.

Fuller’s traditional idea of the war is that it can be reduced to a single question: to kill or to be killed. The rest would be mere intellectual chit chat. An idea as irrefutable as it is shortsighted. Yes, his films have always revolved around the question of identification (to another, to an ideal, to the ideal other) and the aberrations of the eternal “I love you, I kill you”. Fuller’s heroes’ double-dealings are protecting them from the horror of an encounter with a double (like William Wilson) which could lead to their death. They are already double. But the war is the moment when, despite everything, this encounter is very possible indeed, when one constantly risks crossing the gaze of the other, of this enemy that is an enemy only by game and by name*. With Fuller, one of the most violent filmmakers, violence is always mimetic. It is the violence of the masks that no longer hold (his entire body of films mirrors the prodigious opening scene of The Naked Kiss: during a fight, a woman loses her wig – she is bald). It is the violence of the ideologies that don’t hold up much better (in the sense that, according to Zinoviev’s strong expression, ideology is something that one “adopts”, as a sort of voluntary mask).

How to end?

The big difference between life and cinema is that at the end of a film, a small bit of writing, the words THE END, strike through an image. This is the truth of the relation between image and writing. Following the itinerary of the Sergeant, Fuller asks himself under which conditions there could be an end to wars. The answer is literal, tinged with dark humour: there wouldn’t be any more wars if only one war could truly end. But it only takes one soldier, somewhere, to ignore the armistice just signed (this is the story of the hero of Run of the Arrow or of these Japanese soldiers still “holding on” to some Pacific islands) to create a fatality of the return of wars. Just one more bullet and the fury of storytelling starts again. It happens twice to the “Sergeant”, in 1918 and in 1945. Fuller’s obsession – the typical obsession symptom –, is the bullet shot one second too late and the war hero turned into a common law murderer. But how can one know that the “war is over”?

The Big Red One, Fuller’s magnum opus, is haunted with the desire to end, to write the words “the end” for good. Hence the final happy ending, moving because improbable. “To kill or to be killed”, this warrant officer’s wisdom, is a false choice. In one way, the one that kills dies too, he commits suicide. He becomes Death itself, which ignores the double game. The double game is what saves mimetic violence: only impostors are alive. Otherwise, underneath the features of the four soldiers of the film, too beautiful and too vulnerable, one must see the face of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. To join in the camp of the survivors, to have killed the other inside oneself, is to be truly dead.

Translators' note: while translating the text with Andy, we toyed with the idea of keeping some French word references in the English text. I've removed them in the final version to preserve fluidity. But, in the spirit of disclosure (and to show the impossible compromises we had to make), we have used "storytelling" and "story" for récit, "contemporary" or "news" for actualité or informations, "concoction" for précipité and "double game" or "double-dealings" for double jeu.