Wednesday, October 18, 2017

Ghatak’s Clunker

Friday, October 13, 2017

The Wage of the Channel-Hopper (table of contents)

One of the least known book by Serge Daney, The Wage of the Channel-Hopper is the only one entirely dedicated to television programs. Daney watched the six channels available on French TV at the time and wrote almost daily about what he saw. It was first published by Ramsay in 1988 and reprinted by P.O.L. in 1993.

The translation of the title is by Nicole Brenez: "Serge Daney's collection of writings on television, Le Salaire du Zappeur was a pun on the title of HG Clouzot's 1953 film, Le Salaire de la peur, which in English was translated as The Wages of Fear. A better translation, then, would involve the word Wages, rather than salary. The Wages of a Channel-Hopper?"

Here's Daney's foreword:

The texts in this book were published between September and December 1987 in the newspaper Libération for a daily column entitled "The wage of the channel-hopper". Most of these texts are reprinted here. The titles are the original ones but the subtitles have been re-written. As for the texts, they have been reproduced with only minor amendments and no real modification.

And, since all things must end, the text Back to the Future has been written exclusively for this book.

Table of contents

Back to school

Thus spoke Channel 5

The channel-hopper is inside the TV

Lajoinie's socks

Uncle Serge's beautiful stories

The Polac effect

M6, the channel that washes whiter than white

Puppet, or half-puppet

Dubbing, original version

Television in the fishbowl

Spotlight on the image

Stage door

The end of the last word

Before the news

The misfortunes of an ideal son-in-law

In Cine-hit, cinema is number one

There are series, and then there are series

Literature, at the service of politics

The bull by the horns

From the star to the celebrity

Mondino, the hip champion

Bonne nuit les petits

Rather, straight out of bed

Sex and its laughter

From the large to the small screen

The look hits rock bottom

Commercials miss the point

Touring the TV canteens

Schoolyard football

Max Headroom, televisual creature

Normandin's brief laughter

The green audiovisual landscape in the morning

TV doesn't compensate for anything

Oceaniques' gamble

Bouvard at dusk

The other "mass" - the real one

Philippe Bauchard's stock rises in value

Once again, the example of the English

Thursday, October 12, 2017

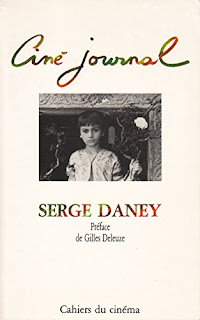

Ciné journal (table of contents)

Ciné journal ("Cinema diary") is Serge Daney's third book. Here's Daney's text from the back cover:

To make a good cinema diary, one needs two things: a diary attending to cinema, and cinema in such a state that it creates a desire to keep a diary.

This diary was Libération between 1981 and 1986, the years when cinema was found to be in crisis. The more we recognise cinema as "the art of the twentieth century," the more we have doubts about its future. At the same time, the more we doubt about the chances of the image in an era dominated by the dogmas of communication, the more we know cinema to be our most precious good, our only Arianne's thread.

A film critic would rapidly become a moralising dinosaur or a museum guardian if he didn't, once in a while, get out of his den. As if he had to work on the cinema-criticism of a world that had less of a need for cinema.

This is why, this cinema diary brings together, day in day out, articles published in Libération. Film reviews, old and new, editorials, reports on current events or travel writing. Travels to the end of the world or travels inside the image, or on television, with its symbols and effigies.

Let the cinema be travelled.

Table of contents

Letter to Serge Daney: Optimism, Pessimism, and Travel - Gilles Deleuze1981

Implausible Truth - Beyond a Reasonable Doubt (Fritz Lang)I, Christine F., 13, Junkie, Prostitute… (Ulrich Edel)

Mr Arkaddin, The Embarrassing Genius

A ritual of disappearance (Giscard)

A ritual of appearance (Mitterand)

Tennis: Balls so Heavily Loaded

Man of Iron (Wajda)

The Death of Glauber Rocha

The Woman Next Door (François Truffaut)

Circle of Deceit (Volker Schlölondorff)

The (Too) Long March of African Cinema

Off Mogadiscio

Coup de Torchon (Bertrand Tavernier)

The Thread (Jean Eustache)

Stalker (Andrei Tarkovsky)

Tarkovsky: The Other Zone

Syberberg in Wagner's Head

The Colour of Pomegranates (Sergei Parajanov)

I Was Born in Calcutta (Satyajit Ray at Home)

Too Early, Too Late (Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet)

The Way South (Johan Van der Keuken)

The best (Xie Jin)

Guy de Maupassant (Michel Drach)

Petit baggage pour Passion (Jean-Luc Godard)

Mourrir à 30 ans (Romain Goupil)

Ciné-bilan de 68

Le Choc (with Alain Delon)

Veronika Voss (Reiner Werner Fassbinder)

Spring Rolls

North by Northwest (Alfred Hitchcock)

White Dog (Samuel Fuller)

Samson and Delilah (Cecil Blount DeMille)

Marilyn

One from the Heart (Francis Ford Coppola)

The State of Things (Wim Wenders)

The Night of San Lorenzo (Paolo and Vittorio Taviani)

Toute un nuit (Chantal Akerman)

Tati, chef (the death of Jacques Tati)

Identification of a Woman (Michelangelo Antonioni)

Japanese Comics: Sake for Children

Moscow: a tour of the cabinet

Moscow: a tour in the box

Impromptu Bergman

Edith, Marcel and Lelouch

Resnais et l'"écriture du désastre"

Ana (Antonio Reis and Margarida Cordeiro)

Ludwig (Luchino Visconti)

The Death of Buñuel

André Bazin

Fanny and Alexander (Ingmar Bergman)

Poussière d'Empire (Lâm-Lé)

Gertrud (Carl Theodor Dreyer)

Rear Window (Alfred Hitchcock)

Rumble Fish (Francis Ford Coppola)

A mort l'arbitre (Jean-Pierre Mocky)

City of Pirates (Raoul Ruiz)

Vertigo - Sueurs froides (Alfred Hitchcock)

Les morfalous (with Jean-Paul Belmondo)

Cannes 1984:

- English TV goes to the movies

- Auteurs: Highs and Lows

- Angelochronopoulos

- The Karma of Images

- Counting Your Chickens

- Vertigo

- Twice Upon a Time in America

- The Quilombo Utopia

- The Winners

El (Luis Buñuel)

The Small Sentence (Youssef Chahine shoots Adieu Bonaparte)

Olympic games 1984:

- New Grammar

- TV Americana

- From the bar

Paris, Texas (Wim Wenders)

The Straubs

Broadway Danny Rose (Woody Allen)

Love on the Ground (Jacques Rivette)

1984 (Michael Radford)

Bayan-ko (Lino Brocka)

The Scorsese affair and the new wave: every image for itself

Les Rois du gag (Claude Zidi)

Staline (Jean Aurel)

Godard, pie in the face at the press conference

No man's land (Alain Tanner)

Our Marriage Really Holds Up (Valeria Sarmiento)

Ran (Akira Kurosawa)

Welles, the love of cinema (the death of Orson Welles)

When Father Was Away on Business (Emir Kusturica)

Que demande le clip?

La Tentation d'Isabelle (Jacques Doillon)

Year of the Dragon (Michael Cimino)

Vagabond (Agnès Varda)

Wednesday, October 11, 2017

Recrudescence - table of contents

It brings together a selection of articles from two columns that Daney wrote for the French newspaper Libération (between October 1988 and April 1991) and a lengthy interview with Philippe Roger conducted in January 1991.

Over the years, many of the texts have been translated, especially with the 30 texts published recently on this blog for the Ghosts of Permanence series. So here's the entire table of contents of the book with links to translations (and the film reference where relevant).

What Out of Africa produces

(Out of Africa, Syndey Pollack, 1986)

Les Baccantes mises à nu

(Ah! The Nice Moustache or Peek-a-Boo, Jean Loubignac, 1954)

Three years after the Dragon

(Year of the Dragon, Michael Cimino, 1985)

The Pirate isn't just decor

(The Pirate, Vincente Minnelli, 1948)

Neo-Tosh

(Marie-Antoinette, W.S. Van Dyke, 1938)

Stella, ethics and existence

(Stella, Laurent Heynemann, 1983)

Cop in a box

(Un flic, Jean-Pierre Melville, 1982)

Minnelli caught in his web

(Cobweb, Vincente Minnnelli, 1955)

That's cinema

(Witness, Peter Weir, 1985)

The last temptation of the first Rambo

(First Blood, Ted Kotcheff, 1982)

‘Wings’ to attempt to land

(Wings of desire, Wim Wenders, 1987)

Archimède's TV drama

(Archimède le clochard, Gilles Grangier, 1959)

Le Diable, maître du scénario

(Beauty and the Devil, René Clair, 1949)

Griffith shows us a thing or two

(Orphans of the Storm, D.W. Griffith, 1921)

The star and the leftovers

(And God Created Woman, Roger Vadim, 1956)

Zurlini, the stylist

(Violent Summer, Valerio Zurlini, 1959)

Un bon Lelouch ? Oui.

(Love is a funny thing, Claude Lelouch, 1969)

John Ford for ever

(She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, John Ford, 1950)

Qui aime Maurice Cloche?

(Rooster Heart, Maurice Cloche, 1946)

Beineix, Opus 1

(Diva, Jean-Jacques Beinex, 1981)

Mad Max, Opus 2

(Mad Max 2, George Miller, 1981)

A true fake Bruce

(Game of Death, Bruce Lee - Robert Clouse, 1972)

Clair, grandad of the music video

(Bastille Day, René Clair, 1933)

The essential Buñuel

(That Obscure Object of Desire, Luis Buñuel, 1977)

Leone at war

(The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, Sergio Leone, 1968)

Rossellini, Louis XIV: the first

(The Taking of Power by Louis XIV, Roberto Rossellini, 1966)

Zurlini, from the back

(Family Portrait, Valerio Zurlini, 1962)

Un Verneuil sans espoir

(La vingt-cinquième heure, Henri Verneuil, 1967)

Alien: come what may

(Alien, Ridley Scott, 1979)

Le roi était nu

(The King, Pierre Colombier, 1936)

Doped up Marilyn

(Let's Make Love, George Cukor, 1960)

Deadly dubbing

(Death Trap, Syndney Lumet, 1982)

Lara inn-keeper

(The Red Inn, Claude Autant-Lara, 1951)

Inusables cigognes

(The cranes are flying, Mikhail Kalatozov, 1957)

Downstairs, étude

(Downstairs, Monta bell, 1932)

Zefirelli, tchi tchi

(La Traviata, Franco Zeffirelli, 1982)

Realist Fellini (Ginger and Fred, Federico Fellini, 1986)

In the water

(Island of the Fishmen, Sergio Martino, 1979)

Laura's aura

(Laura, Otto Preminger, 1944)

Heavens, a telefilm!

(Silas Marner, Giles Foster, 2985)

Sissi impératrice

(Sissi, the Young Empress, Ernst Marischka, 1956)

Citizen Cain

(Citizen Kane, Orson Welles, 1941)

The Dumbo case

(Dumbo, Walt Disney production, 1941)

Illegal history

(Moonlighting, Jerzy Skolimowski, 1983)

Walsh draws kings

(The King and four Queens, Raoul Walsh, 1956)

La vie est un Donge

(The Truth about Bebe Donge, Henri Decoin, 1952)

Sink the Herring!

(Sink the Bismarck!, Lewis Gilbert, 1960)

A touch of Hell

(Inferno, Dario Argento, 1986)

Colourful DeMille

(The Ten Commandments, Cecil B. DeMille, 1956)

Liliom's arms

(Liliom, Fritz Lang, 1934)

Interview with Philippe Roger

Les loges des intellectuels

For a cine-demography

A critical time for criticism

Autant-Lara n'est (vraiment) pas une merveille

Quand le rythme vient à manquer

Catéchisme audio-visuel

Le cinéma et la mémoire de l'eau

l'"Amour en France", et nous et nous et nous

Nicolae et Elena lèguent leurs corps à la télé

In stubborn praise of information

Le tour de l'info en voiture-balai

Uranus, mourning for mourning

Beauté du téléphone

Montage obligatory

Wednesday, October 04, 2017

Liliom’s arms

Lilion's arms

‘I’m sorry we didn’t have the chance to meet sooner,’ says Goebbels. - ‘Yes’. - ‘Will you have any trouble finding the way out?’ - ‘No’.

This is how (in the strange Langopolis) a young American scriptwriter imagines the end of the famous dialogue between Goebbels and Fritz Lang. The latter does so well at finding the way out that a few minutes later he’s on a train bound for Paris. This is 1934 and Lang will never be the boss of Nazi cinema. On the 17 h 30 train, en route for Paris Gare du Nord, Lang is already the man who will turn the cinema against itself and denounce punishment with the very weapons of surveillance. The first director to have seen the threat of the audiovisual panopticon, the first moralist of the media yet to come, he leaves nascent television to Leni Riefenstahl and to Triumph of the Will. He will have his whole ‘American period’ to prove that cinema can, through ever more rigour, be useful.

This is why there’s nothing more useful today than seeing Fritz Lang’s films again. And seeing them again on French television. Just as TV’s awash with reconstructed trials and mass-video redemptions, before the televised re-enactments of the trials of Petain or Barbie, it’s good to go back to Lang, who filmed a lot of trials and who, frequently, cited cinema as a witness. If the trial in Fury is better known than the one in Liliom, it’s because Liliom (1934) is a little seen film and, on the surface, not typical of Lang. It was adapted from the play by Molnar and filmed in Paris for his friend Pommer before leaving for California. The other thing is that the trial in Liliom takes place not on earth, but in heaven.

Liliom is a harmless hooligan who proceeds through life like a Parisian ape man who never knows what to do with his arms. These are the arms of Charles Boyer, arms made to hold more than one woman, and which therefore know not what to do with the fragile body and stubborn love of Madeleine Ozeray. Liliom lets himself be persuaded by Alfred (the great Alcover) to get involved in some nasty business, which goes so awry that Liliom’s arm can find nothing else to do but to stick a kitchen knife in Liliom’s heart, and he dies.

Lang wasn’t the kind who believed that death wipes out wrongs that need to be righted (‘That would be too convenient. What about justice?’). This is why Liliom, his corpse still warm, is arrested for a second time (‘We are God’s police’) by two pre-Wenders angels. Far, far away from Earth, the dead man is escorted to a celestial police station where the personnel (equipped, it’s true, with little wings) is the same as on Earth. Liliom, arms still dangling, guileless and truculent, struts in front of the police chief to no avail. To no avail, since the latter has an unprecedented card up his sleeve, the card of cinema.

And so out of the celestial cinematheque there looms the film-as-a-witness of the life of Liliom Zadowski, and one scene in particular. On July 17, at 8:40am, Liliom slapped Julie because she’d let him drink all the coffee she’d made for them, so as (he says) to blame himself by setting herself up as a victim. The audience has seen this scene in Liliom and already found it beautiful, as they have found beauty in all the scenes played by two characters (with Lang’s camera, which sometimes will go straight for a detail before letting go). Now they see it again, in a private screening and in the company of Liliom, who is flabbergasted. But this time they see it as a jury or, let’s say, as film critics. What they’re saying now isn’t that Lang has style and that this style has what it takes, they’re asking themselves what this style is for, what is the use of this camera homing in and this eye seeking out a viewpoint to adopt.

Lang was proud, but not so proud to compete with the Eye-in-chief of the divine gaze. Anyway this eye is an ear. Man invented the restless body of silent cinema, then the satisfied speech of the talkies. Man did not invent the resonant thoughts of a deaf cinema. In his wisdom (and in his own cinematheque), the Good Lord alone has the truly original version, with Liliom’s thoughts explaining Liliom’s arms; the thoughts that just need to be heard for these arms to become human. Indeed, throughout the whole of the scene-as-a-witness, his inner voice was reproaching him, and it was in self-disgust that he struck the woman whom he loved without being able to tell her so.

It is the cinema that saves Liliom (and which we’re beginning to miss so dreadfully).

First published in Libération on 17 January 1989. Reprinted in Devant la recrudescence des vols de sacs à main, Aléas, 1991.

Part of the Ghosts of permanence series.

Tuesday, October 03, 2017

Colourful DeMille

When the Eternal (tired to be off screen) finally talks to Moses, he wears a beautiful spinach green tunic. This green is profoundly different to the apple green gauze underneath which we feel Nefertiti is naked. It’s not the grasshopper green of the tutus worn by a bunch of dancers. Nor the earth green of the cloud that kills Egypt's first-borns, nor the bleached green of the Red Sea when it opens up. Nor especially the beautiful turquoise blue of the headdress of the spineless Baka. This turquoise blue is the type you can still find in very old prints of the National Geographic Magazine. For anyone who is overwhelmed by a colour chart, The Ten Commandments (1956) is more a story of colours than of taste. DeMille’s taste is what it is but the colours are of a different nature, a nature loved like never before by the late Technicolor.

If Cecil Blount DeMille, a filmmaker little known and without a great reputation, ended up being recognised, it’s less for the religious feeling that his films are strangely devoid of than for the way he tirelessly was able to talk about belief. With DeMille, you only believe what you see, and you only see colours. The man that turns the acid green Nile blood red must have a very powerful God on his side. And a God who sends a teaser in the shape of red cloud followed by a green halo on a mountain, knows that Moses is not colour blind.

To believe in colours must have been easy after the Eternal had invented Technicolor. It would be harder today as the colour in cinema is everywhere ugly and unremarkable. There was a time when the gelatine of the three positives could be impregnated with the right dye and the matrices were quite happy to discharge their colouring on the mordanted surface of the silver halide film*. Colours then demonstrated a rock-solid stability. Seeing again The Ten Commandments is to understand that DeMille was not only the bigoted and reactionary tyrant who liked to see all his flock of extras piled into a single image, but also the kitsch aesthete that took the liberty to treat colours as extras.

Stability is the right word to talk about this damaging filmmaker. DeMille is the man of belief, and of blind belief. But also the man of blindness, because blindness is also a belief. In the end, he talks less about sacred love than pagan love and if The Ten Commandments only contained the thoughtful Moses’ saga, the film would be a short one. Thankfully there are these surprising characters, among others: Nefertiti, Ramses and Dathan. These ones are, in a sense, ‘incredible’. The Hebrew God multiplies stunning miracles in front of their eyes and they couldn't care less! Nefertiti can’t see she’s boring Moses, the Pharaoh can’t see that his people are in danger and Dathan finds a way, two seconds after the Red Sea closes back, to continue to excite the people against Moses. Stubborn love, boasting arrogance, and constant nastiness become the real passions. The passion to see nothing of what stands out so obviously. They are as stable in their blindness as the colours of the film are in their stridence.

In fact, DeMille’s real serious topic, the one he doesn’t deal with and perhaps never even suspected, was composed by Schoenberg in 1932 and filmed by Straub in 1974. It’s Moses and Aaron, the eternal (and painful) story of the quarrels between writing and image. If René Bonnell, thanks to whom we managed to see again (on Canal Plus) the Cecil B version, was logical, he would now schedule the Schoenberg-Straub version, and would thus contribute to the work of civilisation. If only to give Aaron his chance. His chance to doubt** and to be interesting.

* Some are pointing out that this description is sexual. Duly noted.

** Unfortunately, Bonnell (René) couldn't care less about this chronicle.First published in Libération on 16 January 1989. Reprinted in Devant la recrudescence des vols de sacs à main, Aléas, 1991.

Part of the Ghosts of permanence series.

Monday, October 02, 2017

A touch of Hell

Bodies that balked at quaking with fear at the cinema can find a belated revenge in the TV screening of horror films. Without a darkened auditorium, fear is no more contagious than laughter. To be afraid you need to know you’re more alone than others and smaller than the screen. The only effect a TV-miniature can produce, gory though it is, is unease. There is unease at taking the guided tour of sites and scenes where, in principle, there was horror and panic. Unease at obliquely entering the intimacy of fear. From Psycho to The Shining, for a while now there’s been nothing more disturbing than ‘site visits’ and those increasingly cinephile and mannerist returns to the ‘scene of the crime’.

In Dario Argento’s Inferno (1979), an architect called Varelli has built three houses and written a book. In the book, he relates how he has made these houses for three ‘mothers’. Mater tenebrarum (the Rome house), Mater suspirorum (the Freiburg house) and Mater lacrimorum (the New York house) are but one whose identity is revealed only at the end of the film. Inferno doesn’t tell old Varelli’s story, but follows a series of characters, mostly young, who are fascinated by the book and are all destined for ridiculously gory deaths. All but one (the insipid Mark) to whom Varelli confides in extremis: ‘This house is my own body . . . and its horror has become my own heart.’ The owner of the house, the single name of the three mothers joined together, is indeed Death, whose scythe and skeleton are centre-stage in the final conflagration.

The amused boredom aroused by the TV viewing of this cult film derives from the way Argento alone has fun with it. A mannerist, he multiplies the signature effects so that every one of his images will cry out that it is stamped with the name of Argento and knows it. Red or blue filters, flattened lighting (Romano Albani), Carl Orff-style score (Keith Emerson), wild discontinuities and soft padding, red herrings and animals of all kinds. This is all pointless but not unlikeable. Thanks to Argento in particular, there is ample time for a bit of general reflection on mannerism in general.

Let’s take one example. At one point young Sara (who, like young Rose, will soon come to a bad end) finds one of the three houses in Rome and, fearing nothing, one night she makes her way into a library that’s open, then into a cellar, where some faceless alchemist (who has a corpse-like hand) turns his back to her before hurling himself upon her. All the same, Sara takes fright and runs away, tearing her dress, gets home, where she asks a neighbour to keep her company, which he does quite willingly before winding up with a knife across his throat and with the reckless Sara quite inconsiderately stabbed. Just as she’s getting out of a taxi opposite the library, Sara pricks her finger on something sharp and inconspicuous (let’s say a nail) attached to the vehicle. It all happens very quickly, even too quickly: a close-up of the nail, a close-up of the nail and the finger, a close-up of the finger with a drop of blood. The odd thing is that this detail has no dramatic purpose whatsoever, since in a matter of moments, Sara will be skewered. The odd thing is that it is too hastily constructed to have any function, even of premonition. The odd thing finally is that the appearance of this nail is virtually confused with the ‘function’ that it has, a function that is rigorously pointless.

The same goes for characters as for objects and for everything in Inferno and in mannerism. It’s a matter of a fake functionalism where things and characters (which are seen like things) are only there to serve no purpose. The passage from mannerism to the baroque is the passage from "serving no purpose" to "only serving the nothingness", the great Nada that needs great dispositifs*. Mannersism, for its part, can choose to be as modest and carefree as a schoolboy exercise. It’s in this respect that the Inferno made ten years ago, was already a film for our times. For if the advertising aesthetic is the serious face of mannerism, the parody of the horror film is its facetious face. You only had to see Inferno interrupted (just after the guillotine scene) by nine commercials in a row to superimpose the two faces of mannerism. For a while now commodities have been filmed like the nail that pierces Sara’s poor little finger: they only occur for the moment they’re good for, except that they’re good for nothing.

* The author cannot help thinking that if once again the baroque were to succeed mannerism, this would only be achieved by dynamiting the space of the cinema or the small screen. Will there one day be some kind of ludic engineering of collective illusion? Perhaps this is something for a new species of creator: an adventurer in communications, a machine of technological warfare, an iron-willed organiser, a transversal agitator. Goude’s parade in July ‘89?First published in Libération on 13 January 1989. Reprinted in Devant la recrudescence des vols de sacs à main, Aléas, 1991.

Part of the Ghosts of permanence series.